Ayr Campus

For two days in the sunny Scottish mid-winter, members of the Multi-Species Dementia International Research Network met in-person and online at the University of the West of Scotland (Ayr Campus) to explore dementia in our multi-species world. You can see the full program here. With the help of our graphic illustrator (Laura Sorvala Illustration) this is a summary the event.

Dementia presents many challenges for humanity, but these challenges are not limited to humans alone. From the laboratory to the care home, other beings are on the scene and affect how we understand, experience, and respond to dementia. We live in a multi-species world yet tend to think about dementia in mono-species ways. Over these two days, we explored how we can challenge that way of thinking and create new opportunities for innovation.

Day 1:

With introductions from Dr Louise Ritchie and Dr Nick Jenkins (University of the West of Scotland) we participants explored our own connections to members of companion species. We talked of the need to move beyond anthropocentricism in how we seek to understand what dementia is and who (or what) dementia affects. Challenging anthropocentrism does NOT mean a return to the days when people with dementia were viewed as “less than” human. It is about recognising the ways in which dementia reaches across species borders; it connects us with members of other species and those beings “have a stake” in how we humans respond to dementia.

Drawing on research with people in late stage dementia who communicate in ways other than words and who are posited as post-verbal rather than non-verbal, Professor Jocey Quinn (University of Plymouth) used posthuman ideas to explore how by challenging human exceptionality (that focus on the ability to articulate in words), such people enter into a more than human realm that facilitates multi-species kinship. More than human relationality across species can be glimpsed, Quinn argued, in the being of those living with post-verbal dementia. This produces a powerful learning experience for carers and families. Quinn concluded by arguing that more research is needed to fully explore the implications of this post-verbal, more than human kinship both in theoretical and empirical terms.

Shifting from the human animal to the non-human animal, Dr Camille Bellet (University of Manchester) explored the challenges of foregrounding animal perspectives in knowledge production. Drawing on findings from her current project, funded by Wellcome Trust, Bellet explored how relational and multisensory approaches can lead to new ways of surfacing the material realities of cows. The advent of sensing technologies and camera surveillance systems (particularly real-time images displayed on computers and smartphones) challenge imaginaries – including our own, as researchers – around human sensory engagements and ways of understanding cows’ realities. Through this inquiry of and with the senses, Bellet is aiming to advance an innovative approach to the study of human-animal relationships in and outside farming.

Drawing on the Dog Talking and Walking Project, Professor Elizabeth Peel (University of Loughborough) explored the so called “pet effect” and considered some of the subtleties of dog facilitated social interaction. Maintaining social interaction is particularly important for vulnerable groups such as people living with dementia. In examining interview data with five people living with dementia in conversation about their relationships with their dogs, Peel thinks dogs may be especially enabling for people living with dementia, both as a non-verbal interlocutor and as a catalyst and meditator of interaction between people.

Drawing on the Animal Research Nexus Programme (AnNex), Dr Rich Gorman (Brighton & Sussex Medical School) explored the complex relations between knowledge, power, and possibility that are emerging as people affected by dementia are increasingly involved in biomedical research. Several of the people affected by dementia, who took part in AnNex saw themselves as having a distinctive perspective and responsibility to non-human others that came with their proximity to research; a sense of mutual vulnerability and enhanced sense of corporeal responsibility. Not all people affected by dementia want to have conversations about animal research. But for those who ‘do want to know more’, Gorman argued, the aim is to ensure that these conversations can be carefully, sensitively, and meaningfully conducted .

Professor Marie Fox (University of Liverpool) unpacked the concepts of “home” and “care” in multispecies relationships within care homes. Her presentation was informed by empirical research into the separation of older people from companion animals when they move to care homes, which was funded by the Dunhill Medical Trust. The project sought to recognise and analyse the multiple losses and harms that such separation entails for both the older person and their companion animal, and the extent to which law can recognise such harms. In this particular talk, however, Professor Fox focused on whether care homes can truly be animal friendly spaces, particularly when an animal cohabits with a human who has developed dementia. Her presentation explored: what a multi-layered concept of “home” might mean in the lives of humans and animals; the challenges of caring for animals in the care home context; and the complicated attribution of legal responsibility for ensuring animal welfare in such relationships and spaces.

Drawing on 15 months ethnographic fieldwork carried out in a Scottish care home, Dr Cristina Douglas (University of Edinburgh) discussed how Animal-Assisted Therapy (AAT) work is infused with moral reasoning and backed up by ethical practice that places the therapy-dog at its centre. AAT work in care homes can become an emotionally daunting task and needs permanent calibration through an ethic of self-care. In this sense, volunteers often practiced a form of humility, by highlighting that the dog does most of the work. The presence of therapy-dogs in care homes, Douglas argued, invites moral reflections and contributes to what the medical anthropologist Cheryl Mattingly (2014) has called “moral laboratories”. Douglas argued that the presence of therapy-dogs implicitly reorients attention toward more-than-human aspects of the care environment, and how these can be engineered to create a more “homely” atmosphere, accommodating lives that can become worth living in spite of cognitive decline. Douglas also highlighted the limitations of Research Ethics Committees (RECs), arguing that ethical underpinnings of AAT in practice can offer a critical perspective on current bioethical frameworks, in which therapy-animals are seen in a utilitarian way without inviting or accommodating ethical reflection. RECs, Douglas argued, can perpetuate a ‘parasitic’ understanding of AAT and encourages a view of therapy-animals as ‘stimulants’, which implicitly devalues people living with dementia’s sociality in their interactions with dogs. Douglas advocates for an approach to ethical review in which animals are taken seriously, as equally – and, in certain circumstances, as even more consequential to shaping social relations that can forge at the end of life with dementia.

Day 2:

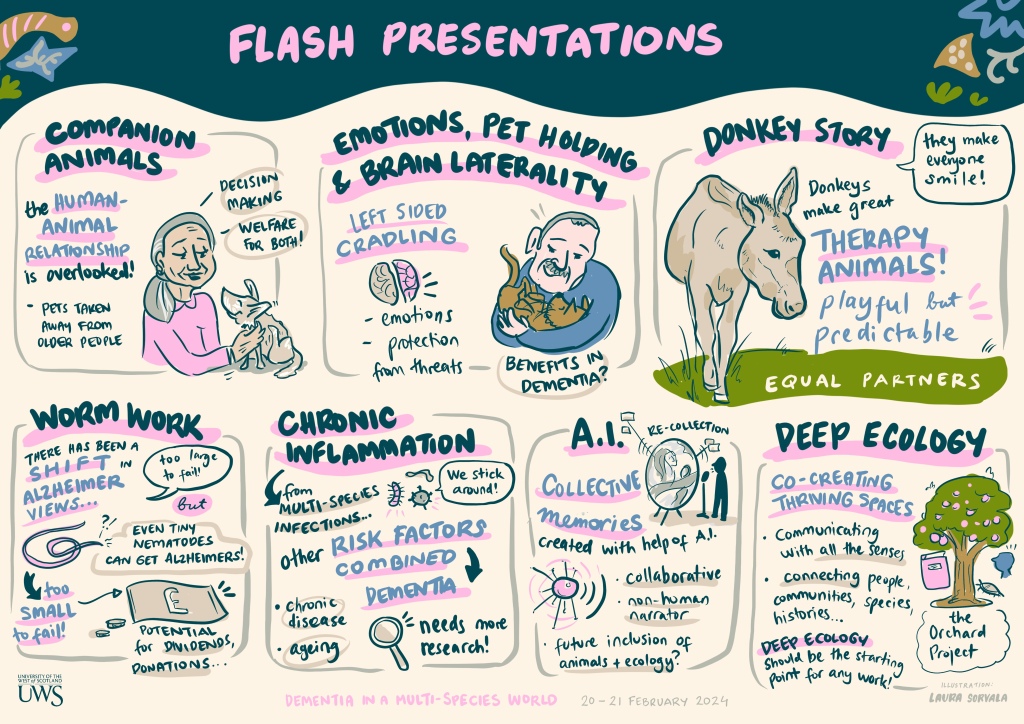

Day Two started with a series of provocative, interdisciplinary Flash talks. Presenters in this session were speaking from a diverse range of disciplines – ranging from sociology to animal welfare, and molecular biology – highlighting the truly interdisciplinary potential of multi-species dementia studies. Flash presenters (left to right) were:

Dr Lesley Jessiman (Scotland’s Rural College)

Dr Bianca Hatin (University of the West of Scotland)

Iriana McGroarty (Farmersfield Rest-Home for Elderly Donkeys)

Dr James Fletcher (University of Manchester)

Dr Anne Crilly (University of the West of Scotland)

Dr Lijaozi Cheng (University of Sheffield)

Dr Timothy Senior (University of Bristol)

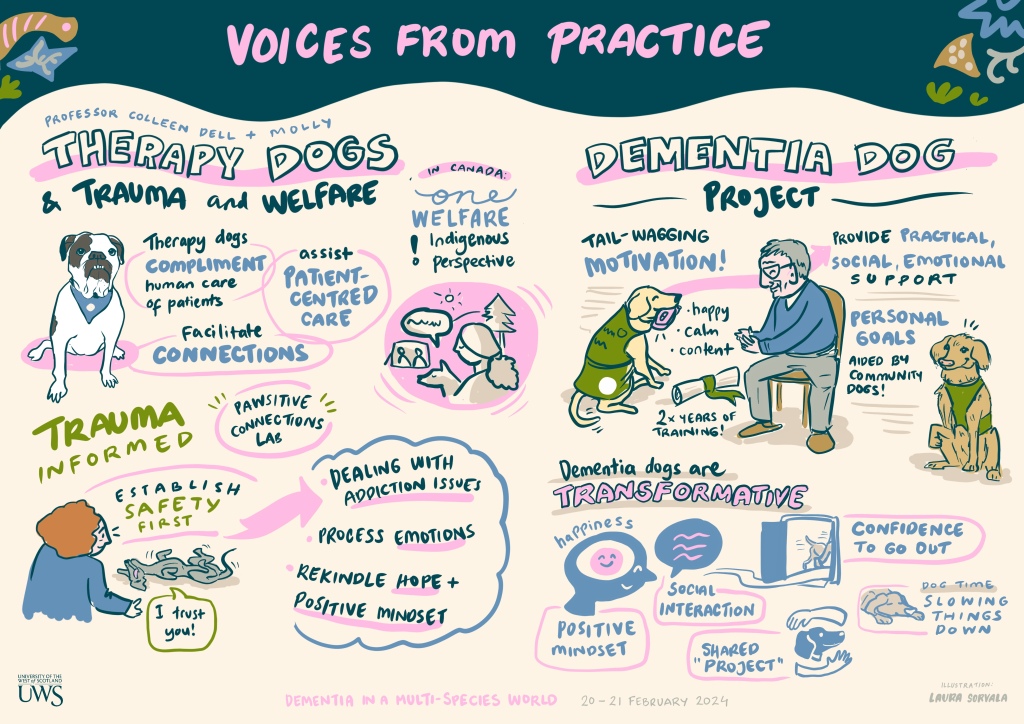

Situated within a One Welfare approach, Professor Colleen Dell highlighted how the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s six evidence-based trauma principles for service providers can be enacted through work involving therapy dogs in a forensic environment, including with patients with memory issues and traumatic brain injuries. We were encouraged to consider like experiences or research examples of trauma-informed therapy dog visits within the dementia field, and Professor Dell shared an online therapy dog handler course which was developed by her team through a trauma-informed and One Welfare lens. More details available here.

Alongside retired service dogs “Uno”, “Webb”, and “Lenny”, Fiona Corner, Anne Rankin, Imke Thomson and Jeannette King shared their experiences, insights and learnings from the Dementia Dog project. Fiona highlighted how Dementia Dog began with the placement of the world’s first dementia assistance dogs in 2013, and has since evolved to offer animal assisted interventions and dog therapy community programs to support people at different stages of dementia, and their caregivers. Through a panel-style discussion, facilitated by Dr Anna Jack-Waugh (University of the West of Scotland), Anne, Imke, and Jeanette discussed the therapeutic benefits that bespoke trained dogs can offer people living with dementia and caregivers. Reports from independent evaluations of the pilot program (here) and the community dog programme (here).

Summary

What a truly fantastic couple of days! In a short space of time we managed to distill many issues central to the future development of multi-species dementia studies. These ranged from the use of animals in biomedical dementia science, to the practicalities and ethics of animals in care homes, and the potential for dementia to create new opportunities for multi-species kinship and bonding. What we have learned from our time and discussions together we can use to forge new collaborations and generate new ideas for research, policy and practice innovation.

If you are new to multi-species dementia studies and you wish to join the conversation, please get in touch via our Contacts Page.

Leave a comment